The Promise With a Thousand Voices

Every now and then, I take some form of class or read some form of article that promises the superpower of range.

Nothing draws me quite so much as a confident headline promising to unlock the secret of generating thousands of distinct characters and character voices. Be like Mel Blanc! Amaze your friends! Roll in money!

By and large, if it’s a quick fix one-off thing and not months of study and rehearsal, it boils down to this formula:

Laban Efforts x (a multiplier) = Many characters

I’m guessing Laban is familiar to some of you, not so much to others, so here’s a quick primer.

Making an Effort and Seven More Efforts

Rudolf Laban was a choreographer working at the turn of the twentieth century. There’s a dance school named after him in London. He is often spoken about in the acting world because among his work was codifying all possible types of effort to eight categories.

In this definition, effort is how we move as opposed to what kind of movement we make.

Let me give you an example. If you move your hand from Point A to Point B, the starting point and destination will always be the same but the journey your hand takes has options. You can move it in one graceful motion, in slow steps, in a line, in a zig-zag, in curves like a snake, etc etc etc.

This is true too for walking across a room, running to catch a train or even telling a story. Infinite ways of doing anything. But each way can be described by one of eight words.

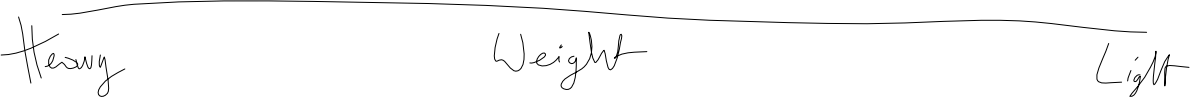

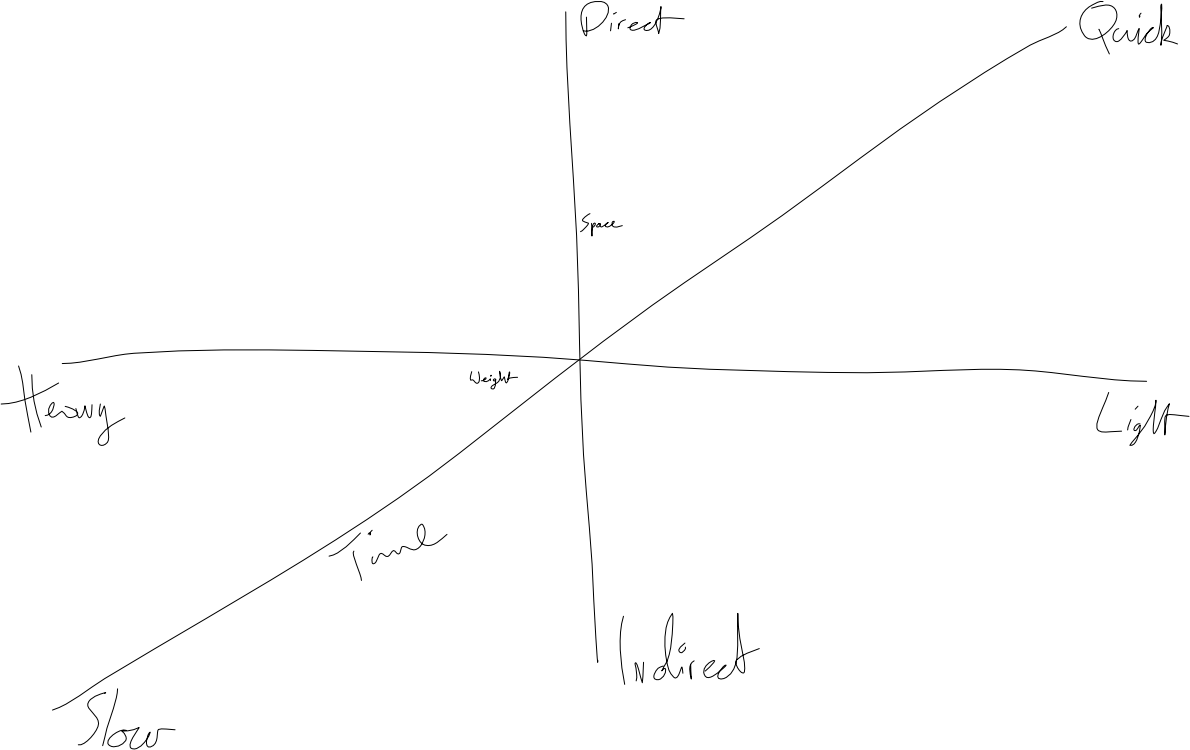

To codify efforts, Laban created three axes: Weight, Space and Time. Each has two extremes. All movements exist somewhere along the spectrum. For simplicity’s sake, we will assume that they can only be one or the other.

The Three Axes:

Weight: Light / Heavy - How heavily a person moves. At one end they waft around like a feather on a trampoline. At the other, they drag leaden muscles across muddy ground.

Space: Direct / Indirect - What route they take to get to where they’re going. On the one extreme they fly straight as an arrow from point A to point B. On the other, they move like a fly buzzing round a room.

Already we can see that it’s possible to be Direct and Heavy like a tractor, Direct and Light like a dart, Indirect and Heavy like a tornado, or Indirect and Light like dust.

Time: Slow / Quick - Or more accurately, Sustained / Intermittent. A sustained (/slow) movement doesn’t let up. Think of a planet turning around a star. An intermittent (/quick) one is fleeting or halting. Dial-up internet.

(I’m sorry, you’re going to have to imagine that third axis in 3D.)

All together, that gives us eight possible combinations. Each has a name.

Light / Direct / Slow: GLIDE (like a hawk)

Light / Indirect / Slow: FLOAT (like a piece of paper)

Light / Direct / Quick: DAB (like a mosquito)

Light / Indirect / Quick: FLICK (like me, confronted with a mosquito)

Heavy / Direct / Slow: PRESS (like a vice)

Heavy / Indirect / Slow: WRING (like drying a towel)

Heavy / Direct / Quick: PUNCH (as in fists)

Heavy / Indirect / Quick: SLASH (like a sword)

Already, we have eight characters. I’m sure you can think of people who glide across the room, people who dab at conversation, people who punch through life. Even clearer than real people are characters in fiction. Alice floats through Wonderland but the Red Queen presses her to stop in place.

So that’s Laban efforts. Eight possible places to start thinking about character. Remember the formula above?

Laban Efforts x (a multiplier) = Many characters

We need to choose our multiplier.

Tabling the Multiplication

We’ve got options here. Age? Let’s assume Young/Old. We’re now up to sixteen characters. Do they smoke? Heavy smoker/never smoked a day, there’s 32. Accent? You get the picture.

One category that’s interested me recently is where we produce our voice from.

Any vocal training, for singing or acting or public speaking, will teach you about vocal resonators. At the very least you’ll likely have heard about breathing to the diaphragm. A concept that I’ve been thinking about recently is linking where in the body we breathe with character.

(I picked this link up at a workshop with Performance Captured Academy. If you’re in London and interested in Performance Capture, check them out.)

The idea goes that there are three broad resonant areas you can place your voice before moving it to the mouth. (NB This isn’t placement in the accent sense which is about placement within the mouth resonators). Sometimes in voice training the back is included as a fourth, sometimes the intercostal muscles are distinct from the front of the ribcage. For simplicity, we’re going to stick to three.

Those three are: head, chest and gut. You may know gut as stomach.

If none of this makes sense to you, try breathing to each of these parts of your body, then releasing on an ahhh sound.

The new idea (to me) was that we can assign specific character types to each of these resonators and then combine these types for complexity. Even more so than with Laban efforts, we are relying on the murky world of narrative stereotype.

I think I need to disclaim that I am more confident about these stereotypes being recognized in the anglosphere than anywhere else, and even within that my main experiences are limited to the UK and the media we get here. But although they exist more in fiction than reality, I think it’s fair to say that some people consciously or unconsciously lean into established stereotypes in order to project a certain image.

The Stereotypes:

In this 2D world, Head characters are Cerebral.

They might be verbally dexterous, particularly witty types. Think John Cleese, Sandi Toksvig or Stephen Fry. Think of the image Jacob Rees-Mogg tries to project. The UK produces these by the bucket.

Chest might as well be called Heart.

Here are your emotions-driven character. They are everywhere in Hollywood. Picture a wide-eyed teenager in an American movie going through their first breakup. Think of ninety percent of the Marvel heroes.

Gut is all about Power.

Politicians are trained to speak from their gut. Margaret Thatcher was a famous example. Watch them on the campaign trail. They slow down. They’re still. They orate. It all comes from their gut. You might also think of the drill sergeant from Full Metal Jacket.

Alright, now we have three new character types to combine with our efforts. We can have Cerebral Floaters, Emotional Dabbers, Commanding Wringers…

8 Laban Efforts x 3 Voice Resonators = 24 Characters

Pretty good. But we can take this deeper.

Doubling Up

To keep our characters from getting too cardboard, we’ll assign them a second vocal placement. This will help us to begin to fill in some light and shade. The first voice is where they feel most comfortable. The second is something for them to slip into. Why? Under what circumstances? Up to you.

Here are the rules: the two voices aren’t allowed to come from the same place, and we can’t cheat and say ‘well everybody uses all of them so I’m going to use all of them’.

We now have six new categories:

Head-Chest (Cerebral-Emotional)

Head-Gut (Cerebral-Commanding)

Chest-Head (Emotional-Cerebral)

Chest-Gut (Emotional-Commanding)

Gut-Head (Commanding-Cerebral)

Gut-Chest (Commanding-Emotional)

That’s all a bit of a mouthful. So I’ve been getting creative.

Warning: from here, we’re leaving other people’s established practice behind and cruising on the HMS Felix’ Shower Thoughts. The good news is those shower thoughts come with a spreadsheet.

To each category I have assigned a name. These names are Archetypes which, for me, seem to fit the bits in the brackets. I’m not looking for nuance, I’m looking for broad sketches.

Archetypes are established characters you’ll find across storytelling. Evil stepmothers, wandering heroes, wise wizards… They tend to be characters you’d recognise in fairytales or Aesop, though some recent ones have emerged (tech bro springs to mind). To keep things as general as possible, I try to use those earlier storytelling words.

My Vocal Archetypes:

Head-Chest (Cerebral-Emotional): Teacher

Head-Gut (Cerebral-Commanding): King

Chest-Head (Emotional-Cerebral): Counselor

Chest-Gut (Emotional-Commanding): Knight

Gut-Head (Commanding-Cerebral): Thief

Gut-Chest (Commanding-Emotional): Warrior

Even if they are general and a bit Camelot, these are some loaded words. Thieves are bad, right? However, the Archetypes have to exist without judgement. There are good teachers, there are bad teachers. There are kind thieves, there are evil thieves.

8 Laban Efforts x 6 Vocal Archetypes = 48 Characters

We’re getting to the kind of numbers where there’s so much information in each character that I’m struggling to hold it all in my head.

Putting it All Together

If we pick one Laban Effort and one Vocal Archetype at random, we have an interesting place to start building a character. Combine, for instance, Light / Direct / Slow with Cerebral-Emotional and I envision a graceful, purposeful, bookish person.

But I don’t want to get too led by the combined Laban / Vocal Archetype names. In this instance, Light / Direct / Slow + Cerebral-Emotional = Glide + Teacher or a Gliding Teacher.

Which sounds like they’re on roller skates.

I would prefer to come up with forty eight new Archetypes which try to capture all five of these qualities while still being instantly recognizable and applicable to new characters.

So that’s what I did.

For simplicity’s sake, I’m going to call these new Archetypes Characters. In truth, they’re about as fleshed out as the initial Vocal Archetypes or Laban Efforts, but I want to differentiate the vocabulary.

In the Glide family, we have Gliding King (Cerebral-Commanding): a graceful yet powerful person. I call that Character the Ambassador.

What about Gliding Warrior (Commanding-Emotional)? Strong and easy-going. For me that’s The Hero.

Gliding Thief (Commanding-Cerebral)? As much as I’m trying not to put too much judgement on them, I couldn’t come up with better than the Scammer. Perhaps you can improve on it.

Sometimes, the best I could think of was an established character. This was the case with our Gliding Teacher, or as I call them, Gandalf.

So I took all of these new Archetypes and I put them in a chart.

8 Laban Efforts x 8 Vocal Archetypes = 48 Characters

So how might we use this?

When and How to Use This

On the one hand, I’ve been using it with multi-rolling. Sometimes we’re called on to find a lot of characters for short one liners. It happens in voice work but also in theatre ensemble and sketch.

If we have little time to prepare and need to find something quick, being able to refer to a chart and pick something you can slot into seems useful to me. I would err on the side of going with the script rather than against, ie looking for the Character which fits best. If you need a different take, you can always look for the opposite and try that out.

On the other, if we’re carrying a role through a longer process and have the luxury of rehearsal, Characters can provide a starting point. Work with whatever tools work best for you.

In more immediate terms, what steps can we take to use or adapt the chart?

Well, I also made this:

Pick your weight, space and time and the corresponding effort will display in yellow. Pick your two voices, and the voice archetype will in red. The two will combine into Character in green.

To use the chart, you need to make a copy of it. Here it is:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/110Yh2P7We8iE-b1mZmPjX4Or1JznvJ9SsEMMn9muqMY/edit?usp=sharing

It is restricted. You cannot use the dropdown menus while it is restricted. Make a copy of it for it to work (File → Make a Copy). I know this works with Google Sheets but if you don’t have one of those, I imagine similar services work in the same way.

You can now play with my Character chart.

Maybe you don’t like the Characters that I chose. They probably don’t all make sense to you. I am limited to my head.

Here’s how you change them:

At the bottom of the sheet, head to the tab marked Archetypes and you’ll find the chart from above. You can change anything in a green box to whatever suits you. It will then show up in the first tab when you make your choices.

I’m sorry to say that you can’t change the Vocal Archetypes in red without breaking the sheet. Unless you’re willing to change the actual code in which case, have at.

So where next?

If forty-eight isn’t enough for you, you might think about what other multipliers you can tag on. If Myers Brigg or enneagrams speak to you, those could be useful. I think there’s a lot of potential in the LeCoq Seven Levels of Tension which would make three hundred and thirty six. If you find me in a month trying to come up with forty eight iterations of the jellyfish, you know what happened.

For my part, I’ve also been using the chart in reverse. It’s interesting to me to watch performances and try to map them back to the chart, then ask myself what it would look like if one quality were to change. I’m surprised at just how often I found a fairly direct correlation. Perhaps it’s confirmation bias.

Do let me know if this ends up being useful. It’s been very fun to make.

News

The podcast Arden are currently crowdfunding. They’ve kindly offered me a couple of roles in their third series. Support them here: https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/arden-s3-midsummer-in-new-york-city#/

This is a great tool Felix, I've already got a copy saved to my bookmarks. Thank you!