How do you learn all those lines?

Break up text

One time, when I was a child, my Dad sang a song.

It was my birthday party. I remember very little about it. I know we were in the heart of Brussels, because that’s where I lived.

I have a hazy impression of small bouncy Belgian friends, of grey skies coming over the garden, of the second living room door which opened thrillingly onto the back of an armchair. I can see the weird high mirrored ceiling above the dining table that gave the impression you were falling up. And my Dad’s guitar, and my Dad.

Who sang:

‘There’s a hole in my bucket,

Dear Liza, dear Liza,…’

The bucket song is a beloved childhood cautionary duologue about a fraying marriage. Liza sensibly suggests mending the hole then goes completely mad and decides the best tool for the job is one single straw. Her husband, a marionette looking for an id who has never come across the concepts of things, encourages her delusion and a laundry list of problems ensues until we return to the central thesis of the perforated bucket. History is doomed to repeat itself. The singer therefore has the opportunity to buy another ticket on this hellscape roller-coaster in the tradition of other children’s epic verse like Charlie Had a Pigeon or The Iliad.

Dad only sang it once, for he is merciful.

And I knew it.

From the moment he finished, I could sing the whole song by heart. This has never happened to me since. I’m not convinced he’s even sung it since, but it seemed that as soon as he started singing, I opened up my head, inserted a new tape and pressed record. I was for the first and possibly only time in my life dead line perfect.

Thinking back to it now as somebody who’s spent slightly more time with gobs of unfamiliar text, learning the bucket song comes with an inbuilt cheat code which is this: this story of marital discordance makes perfect, torturous, maddeningly detailed sense.

How so?

Each step leads to the next in a very simple and obvious fashion. So long as you understand the story, you quickly absorb the steps of that story.

Hole in the bucket → Mend it

With what? → A straw

Straw’s too long → Cut it

With what? → A knife

Knife’s too blunt → Come on Charlie Sharpen it!

With what? → A stone

Stone’s too dry → Jesus Christ WET IT

With what? → Water

With what shall I carry it? → I still have my old bank account A BUCKET

But there’s a…

And on we go.

Making sense

There’s this question that comes up sometimes. For people who have other jobs, if they think about acting at all they can tend to think of it as a memory test. They remember when they had to learn Wilfred Owen at school and make the quite sensible connection that it must be a bit like that.

And it is.

A bit.

How do you learn all those lines?

Fair question. Scripts are big. Even small scripts are big. They are, generally speaking, too much text for one person to look at and just absorb.

But there can be a misapprehension here. While, yes, you do need to get the lines out of your mouth sans text if it’s that kind of production and generally pretty sharpish, the difficult mistake to get your head around is believing that the job when you’re not onstage, on camera or on mic1 is about learning the lines rather than understanding them.

Get This

Let’s talk about units.

Alright, I get it, you hate units! They’re such a slog. Or you’ve no idea what I’m talking about. The vocabulary shifts around depending on where you are and who you’re studying with. You might know them as beats or French scenes. You might believe a beat to be a subdivision of a unit or vice verse. You might come from writing where the vocabulary is once again the same but subtly different. It doesn’t matter. They all serve the same function. I shall continue calling them units. You call them whatever you like. A definition we can probably all agree on is that they are divisions of the text created by the actor or director but not the writer.

When you are presented with text, it is typically divided up for you into Acts. These Acts, helpfully, come with their own divisions called Scenes.

Acts allow us to quickly tell the story by saying that First X happens, Then Y happens, and Finally Z happens.

Scenes allow us to do the same within an Act. For X to happen, First A has to happen, Then B, Then C, and Finally D.

Acts allow us to zoom in. Scenes allow us to zoom in further. These are very helpful things if you are creating a production schedule or studying for A-level.

When presented with a scene though, that’s still rather too much text to just, like, get. We have to be able to zoom in even further. So we create our own divisions.

Divide and Cogitate

I am not here to tell you exactly how to divide things up. I will tell you what I currently do but no two people agree on this and all are absolutely certain that their way is the only way anybody is doing it.

The problem is we all have differently wired heads.

Here’s what I works for my wiring:

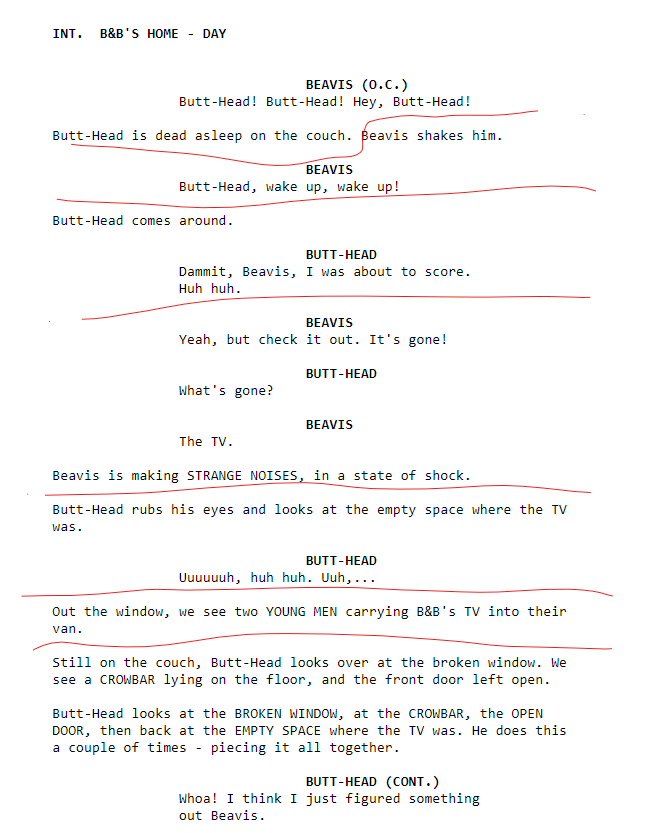

Take a scene. Let’s find some old classic to play with, a key oft-quoted text that lives on the syllabus.

Perfect.

To mark a unit, I’m going to draw a line at a point it looks like there is a big change. For example, Butt-Head coming round.

We now have two units. One before Butt-Head comes round, one after.

I will go through the whole scene looking for units and draw lines. But… how do we know what is or isn’t a unit?

I have one non-negotiable and then everything else is up for grabs.

Imagine you’re at a small dinner party. There are four of you having a conversation around some crisps. You’re talking about something very deep and interesting, like crisps. Then a fifth person enters the room and sits down.

The dynamic has shifted. At the very least they need to be caught up on what was just said about crisps but perhaps they are late to the party and have a whole topic of their own they want to bring up. Like olives.

Now imagine someone else gets up and leaves. The dynamic shifts again. You say your goodbyes and the remaining four can finally stop talking about crisps and olives and start on the real business of planning a coup. (Or nuts).

My non-negotiable is someone leaves or enters the space.

People entering or leaving the space cannot but help affect that space. But when we get confronted with them doing so in text, it is far too easy to overlook this because it’s just a line of text among others; we see the change in the text but not in the texture.

For the sake of our example let’s assume that because Beavis begins off screen, he arrives in the room between the calling and the shaking.

We now have three units.

Beavis is looking for sleeping Butt-Head.

Beavis wakes up Butt-Head.

Butt-Head is annoyed.

Beginning, middle, end. A story!

But what if there’s nobody arriving or leaving? Your mileage will vary. I’ve heard it’s when the topic changes, or when the emotional charge is different, or when someone tries a new tactic to get what they want… What’s important is that it’s whatever gets you to a place of fully understanding the story. I have worked with people who won’t draw a line for three or four pages and others who cover their pages with lines.

For the current text, mine will look something like:

Beavis is looking for sleeping Butt-Head.

Beavis wakes up Butt-Head.

Butt-Head is annoyed.

Beavis tells Butt-Head the TV is gone.

Butt-Head takes it in.

The men put the TV in the van.

Butt-Head pieces it all together.

This is a much more detailed and useful map to the actor than:

Scene 1. Beavis wakes up Butt-Head because the TV is gone.

It allows us to look at each moment separately and work out why it is a logical follow on from the previous one and understand the story more thoroughly and speedily.

And guess what.

It gets even more granular. If you want it to.

Once we have a good idea of what is going on in the scene story-wise, we are down to questions of precision. We can take each unit and look at it sentence by sentence, punctuation mark by punctuation mark.

So. Let’s say I have unitted and got a good understanding of the story. But something’s still not clicking for me so I want to go deeper. What could that look like?

There’s this version:

That’s helpful to some people’s wiring. Sometimes, I like to rewrite it in a way that gets rid of all the furniture in the script I’m not using:

As I look at this list, the thing that jumps out at me is that little ‘Hey’. They’ve not chosen to write ‘Hey Butt-Head!’, they chosen to write ‘Hey [comma] Butt-Head!’ As a wise friend told me recently, sometimes punctuation is just punctuation. You can absolutely treat that as ‘Hey Butt-Head!’ and nobody will think the worse of you but the comma being there means we have an opportunity to play with that Hey as its own little cosmos.

We’ve gone beyond units, by the way. That’s why I prefer thinking about how you divide it all up than strict definitions of the vocabulary. Bold is the director who wants to treat every half sentence as a unit - this is just extra fun for you and me.

When to Divide

You will find people who insist you use units or similar in all your text work. People who want you to mark out your objectives and superobjectives and actions and obstacles. They’re geniuses of course. You will find people who are adamant that they serve no purpose except to make you feel like you’re working and you should do it this other way. They are also geniuses. We are blessed with so many geniuses that we can take what works for us individually, and discard the rest.

Once we’re alone, we are geniuses. And it’s up to us to play in our genius workshops and figure out what works for us. If all you’re doing when presented with a script is highlighting your lines and then saying them a lot rather than trying out the tools, you’re making things both much harder and much less fun for yourself.

(And please have fun.

Or what’s the point?)

And if that doesn’t work, try something else. How you learn all those lines is ultimately down to the fact that you care to do so more than somebody who has not chosen this job. You might as well ask a plumber How do you seal all those pipes?

I don’t unit religiously, but it’s a tool I sometimes break out of the box when I’m struggling with a scene. And sometimes it helps, and sometimes not.

The goal is not the text divisions, but they can help with the real goal: to make the story make perfect, torturous, maddeningly detailed sense.

News

Hello again, I’ve been off Substack for a few month because, quite honestly, I had nothing to say and you have enough newsletters in your inbox to delete each morning as it is. Instead of monthly, let’s call the frequency of this newsletter every sometimes for a while. Perhaps it will pick up.

But in that time, a bunch of great people I know have joined the platform, all of whom are writers. If you want excellent insights there, check out:

Yes, technically we have our scripts with us for mic work and sometimes get it five minutes before recording. The principle is still the same. You do what you can.