An element I find endearing about the actor-audience relationship is that it cannot exist without care. Mutual care even. You look after us, we look after you. The show engine needs both to run and if one side breaks the agreement, it stalls for both.

That goes for recorded media and live. A film, game or audio drama needs your attention as much as anything on a stage. If it plays to nobody, it all get a bit existential.

The audience expresses that care by ceding the space to you, the space here being both the physical space and mental. They allow you, as storyteller, to take charge of their focus for somewhere between 22 and 180 minutes of distraction, laughs, catharsis, education, whatever. In exchange for being given that space, you exercise your care for them by taking it. You give them time to not have to make any decisions for a while, just watch and/or listen. What a gift!

And yet.

Have you ever been in an audience where you felt that most of the work came from you? That you, a paying spectator, were on some inscrutable level being given the job of cheerleader, that you were laughing that little bit louder or clapping and whooping that little bit more to compensate for a flagging show? It feels like everybody’s doing their job but somehow the engine is spluttering.

Let’s talk about Trust.

Anti-Trust Flaws

Although a show cannot exist without care, it can exist without Trust. But it will do so painfully until that Trust is found again.

You will find it easier to perform, to be creative and spontaneous and have fun, if you can rely on everybody in the space with you. To be specific, three bodies. They are:

Body 1: The Audience

The nice thing about an audience that doesn’t audient is that once they stop audienting, they are no longer your concern and either you will never know about it because you hopefully don’t get notifications every time somebody changes the channel, or it is up to the venue to eg fire a crossbow bolt into their phones.

Body 2: Your Colleagues

Take the number one and divide it by the number of people on stage. When you are performing, irrespective of the size of your role on paper, that fraction is how in charge you are. Three of you? You are one third in charge. Eight? You are one eighth in charge. Just you? Hail, benevolent leader. What that leadership fraction looks like will differ from company to company and production to production. If you’re lucky, you’ve had a rehearsal process.

That rehearsal process exists partly to build trust between a team who might not have met. If you’ve ever scoffed at the idea of name games or chucking sound balls at each other, consider how these activities foster a sense of discipline and play among strangers, and how much more daring their choices will be over time, or how much more ownership they feel over the show.

Once we get to performance, an ensemble who trust each other will find it easier to share leadership than one who’s still figuring each other out. Just ask the Lions.

Body 3: Yourself

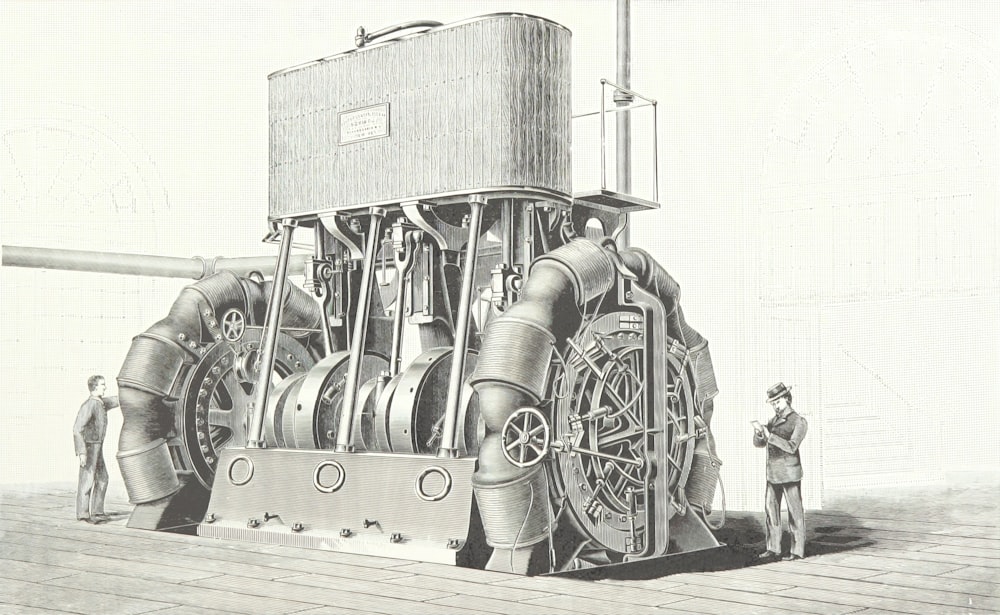

Here’s an illustrative volcano.

When a performer doesn’t trust themselves in a performance, which can happen for all kinds of reasons but often it’s because their work is not being received in the way they pictured, I’ve seen (and experienced) it go one of two ways. Let’s call those implosions1 and explosions2.

Implosions

An imploding performer reacts to their nerves by shutting down. They become a ball of quiet and stillness, nimbly ducking the spotlight and hoping that freezing will save them from the T-Rex of audience attention. It doesn’t. I remember this happening to me once in an improvised scene when a rather drunk scene partner decided to take things in an uncomfortable direction. I didn’t trust him to take care of me as his colleague and I didn’t have the experience to trust myself to take charge of the situation. I grew quiet, my shoulders sagged, I stared at the ground and waited for rescue. It can’t have lasted more than thirty seconds but dear god can I not remember anything else about that show except that I spent it attempting to become one with the building for the whole rest of the time I was onstage. I’m sure I tried to be a useful member of the company and I’m equally sure that I was not.

Explosions

An exploding performer reacts in the opposite direction, with a less reliable outcome but always the same impetus: everything’s wrong and it’s up to me to fix it aaaaaaaaaah! This can manifest as forcing lines, speeding up unnecessarily, clowning, mugging and attention-drawing, or myriad other ways that break the ensemble. That one over number of performers fraction dissolves in their hands and heads. Once they’ve got going, it is hard for them to stop because they have set the bar to frenetic and the scariest thing in the world is to stop, take a breath, and move on. This results in less and less focus on whoever they are sharing a stage with, inevitably rushing beats, skipping jokes and treading on lines. Dear god, have I exploded enough times to recognise this3.

What often happens next is a seesaw effect, with some of the performers exploding and others imploding to compensate. Or some start to retreat and the others panic. The stage is out of balance. (I am using stage in the broadest sense - it as true in other media than live performance).

Whether you are imploding or exploding, the root is a lack of trust in yourself. You will most commonly find unbalanced stages among groups who do not regularly perform live or haven’t done it in a bit. When performers speak about feeling ‘rusty’ after a spell away from working with live audiences, what they mean is that they no longer trust themselves in that space. The solution is the scariest thing: recognising what’s going on and reminding yourself that you’ve got this.

Balancing the Stage

Here’s the thing. Unbalanced stages happen. All the time. And if you find you’re imploding or exploding, nothing can be gained from recriminating about it, especially not in the moment. The more you turn on the self-hate taps, the harder it will be to recover or try again because your focus has shifted. Unless you are Cirque du Soleil and have been performing the same show with the same group of people night after night for months and years, the likelihood is that you will always have unbalanced moments. That’s not the problem. The problem is getting back to a balanced state and to do that you need to bring your focus back to where it belongs.

That is on the action, on the given circumstances, on the relationships and just enough on your surroundings as an actor, enough so you hit your mark or don’t fall off a stage or don’t impale yourself on a microphone. On being alive to the show, not how the show is being received. To do that, you need to trust yourself enough to stop thinking about yourself. If you’ve got this, you don’t need to monitor how every line lands.

Once you trust yourself, you’ll find that you remember to trust your colleagues. You don’t need to solve everything if you are a fraction of a whole.

The Trust Fund

So where do we get this boundless resource of self-trust?

I might as well ask what is the secret of confidence? Self-belief? Charisma? The X Factor? Castability? Funny Bones? It? It goes by all sorts of names maybe because it’s embarrassing to admit how basic and practiceable a skill it is, maybe because people in the arts want to scare away the competition by making the work seem ephemeral.

I can’t answer for you specifically but for me it as basic as experience and practice. The more I work, the happier I am keeping my focus where it needs to be. I also need to be comfortable with the knowledge that I will slip up or my performance will at times not land. Because if I accept that every specific performance won’t work out, I give myself space to trust that my general trajectory is on the right track.

Whatever the process for you, if you find Trust enough in yourself as a performer to keep your focus where it belongs, you will be taking charge, balancing the stage, and allowing the audience to embrace the gift of switching themselves off, not you.

News

Wooden Overcoats won Gold for Fiction at the British Podcast Awards, woo!

Not many good royalty free pictures of this.

Volcano.

A side note to this: don’t confuse performance size or stakes for forcing or pushing. “So long as you’re grounded in reality, there’s no such thing as ‘too big’.” - Uta Hagen