I used to be very worried about crying.

I worried about it for one reason and then, as I got older and started working as an actor, like all good startups I pivoted and worried about it for the opposite reason.

For most of my growing up years in nineties Brussels, a steady drumbeat of messaging made it clear that crying was an unbecoming feature in boys - particularly thin British boys with Reithian accents, an aversion to football on health grounds, and a conviction that, where growth spurts were concerned, 1m70 was too ambitious. Those of us who indulged in crying (including the demographic known as ‘children’) would lay ourselves open to other fun -ings like laugh-, insult- and punch-. So, when I was about eleven or twelve, and after a particularly embarrassing tearful and public classroom episode which, on later reflection, probably owed something to getting up before dawn every morning in order to carry half a metric ton of books to, from, and around my school, I put childhood tears in a box and threw that box down a deep, dark well.

For a while, this worked.

But.

Unknown to me, young Felix was out of sync with the turning of popular opinion on this matter back in the UK. Around about when I was deciding to move on from the whole emotions business, Diana died. The new prime minister Tony Blair used this event to form a working group with Elton John in which they decided to thwart me personally, and decreed that it was now unBritish not to cry. The country nodded sagely and, as one, chose to replace the then national pass-time of discussing the presenters of interior design shows with the much more exciting new one of non-stop weepery1.

A few years later, I became an actor.

And, as it turned out, while the Blair-John directive was being implemented and the British people applied for grants to have new tear ducts installed, a strange belief starting to permeate spaces where acting happened, one that we are not fully rid of today and that I’ve only recently started to unpick from my own head.

That belief is a particular definition of Good Acting.

Is it the truthful meeting of actor and text?

No.

Is it a playful flexibility and willingness to explore?

Also no.

How about reliability, preparedness, a script covered in obscure hieroglyphs, lungs that can sustain three hour performances eight times a week for several months, and a malleable attitude to the time known as ‘dinner’?

It’s not that.

The belief runs that Good Acting = Crying.

Spontaneous, beautiful, pearlescent tears glistening the second they are summoned by script, director or simply the movement of the ether. Somewhere along the line in my first years as an actor, I absorbed the idea that if I couldn’t make my cheeks glisten at the snap of a finger, I had no business in The Business.2

I think we can see where this wire got crossed. We praise the idea of vulnerability in acting, we do so in all the arts, and what is more vulnerable than being reduced to tears?

(Quite a lot).

I have a distant memory of a French director years ago telling a class I was in that if you can’t cry on cue, you can’t act. It’s the kind of unprovable word trick that worms its way into the brain and rots it from the inside.

Staying safe from word tricks.

I live in London. There are many good things in London, like the thrilling old school bounce of the seats on the Bakerloo line, or the fairytale glass-walled lift in the Southbank Centre, or the sunset song of the Evening Standard distributor. There are things that add a little sag to my shoulders too, like the way my nearest big Tesco seems intent to o…

‘How do you cry on cue?’ is one of the three breathless questions that leave many people reeling at the Good Actingness of it all. They are asked in a tone that implies you have x-ray vision or flying powers or… whatever Batman’s superpower is3.

How do you learn all those lines?

How do you do accents?

How do you cry on cue?

You might as well ask a carpenter ‘How do you build a house frame?’ or a barrister ‘How do you remember all that law?’ The answer to the first two is: ‘I have done a lot of work and I will continue to do a lot of work. The work is interesting to me but probably boring to you. I’m sorry that I don’t have an easy trick to teach you.’ And I suspect the answer to the third is: ‘That’s the wrong question’.

The Right Question

I had it in my mind that the way to get the result I wanted was to Dig Deep. By sitting with my emotions, head bowed, sad songs playing, watching the first fifteen minutes of Up on a loop until I could re-enact it, some part of me would suddenly give award winning performances to stun the world and, crucially, get me lots of paid work.

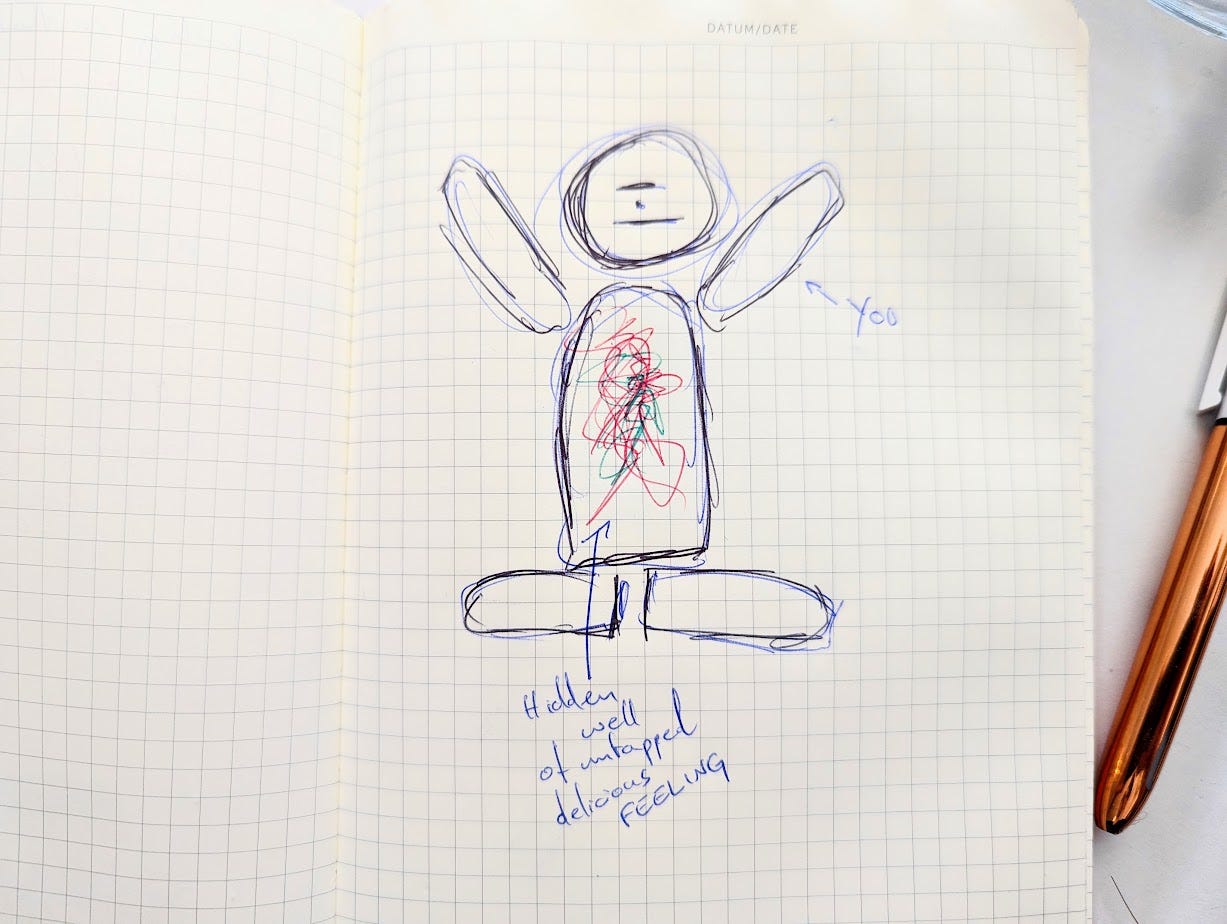

This conception relies on the idea that feelings come from within. Somewhere at our core is a useful seam of emotions we can mine as needed, if only we focus on it properly.

But my mistake was having a ‘result I wanted’.

The problem I have with Dig Deep is that it assumes acting can be done solitary. But I refer you to the title of today’s newsletter.

If we rely on ourselves alone to find a truthful interpretation of the text, we are not focusing on whoever it is we’re talking to. It’s the old ‘are you listening to me or thinking about what you’re going to say next?’ problem recast for performance.

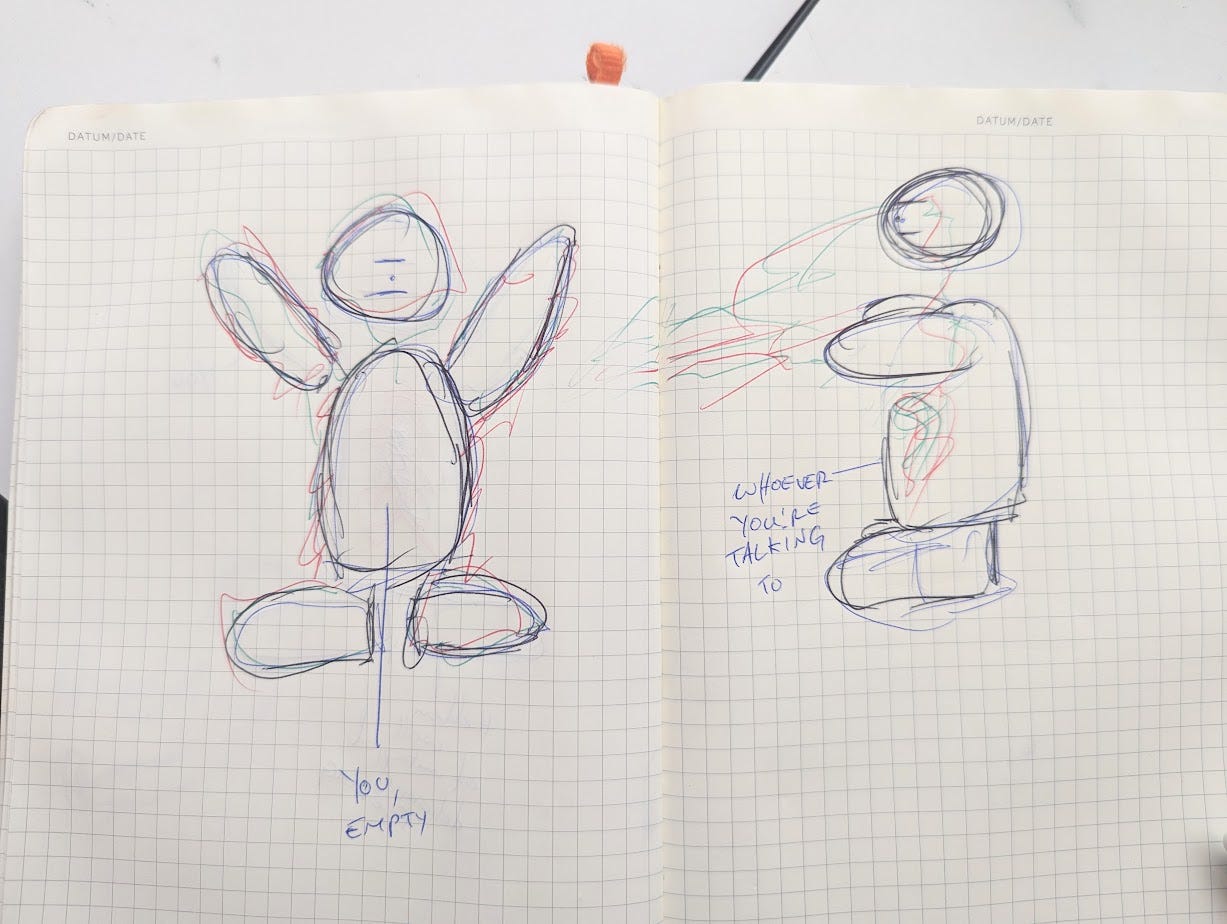

When you’re doing your prep, the above may well be a helpful image to you. But when you’re on your feet with the other actor(s) or audience, I think that image has to give way to a new one.

In the most literal sense, I feel with my skin, not my lungs. So the first shift in conception for me was to stop looking for some buried organ that holds all past experiences in one unlockable form. It’s not there. Don’t dig deep, dig shallow.

The second shift was to stop worrying about what I’m feeling and what reaction it produces. If that’s what I’m doing, I’m not worrying about the person I’m talking to. My objective, my attempts to change them, my tactics, whatever you want to call it… has gone out the window. I am interested in the spotlight falling attractively on me and giving a perfect performance4.

There is no such thing as a perfect performance.

So long as you focus on what you want something to look or sound like (and please note, I am talking about in performance, not when you’re doing your earlier script prep for the which, please, go all director mode so that your subconscious has things to draw on later), even if you are a person who can magically cry on cue, you will not be vulnerable.

Vulnerability is not the accurate portrayal of sadness, or joy, or fear or whatever. It is not knowing exactly what is going to happen next. It is continuously trusting and finding it in the eyes of the person you’re speaking to. It is scary, you should feel like you don’t know what you’re doing; my favourite actors tend to have a slightly baffled look when they’re not performing. If you need to imagine a well of feeling, try imagining that well within your scene partner.

If you don’t believe me, let me come at this from a slightly different angle: have you ever felt home-sick?

I have. I can have all my needs taken care of, any fears abated, and yet the discomfort of a new surrounding can make me long for the familiar. Almost like invisible tendrils are drawing me back.

Invisible tendrils is a very good and useful image, one I’ve nicked from Douglas Adams.

Every being in the universe is tied to his birthplace by tiny, invisible force tendrils composed of little quantum packets of guilt. If you travel far from your birthplace, these tendrils get stretched and distorted. […] This would mean, in these days of hyperspace and improbability drive, that most people’s souls are wondering unprotected in deep space in a state of some confusion, and this would account for a lot of things.

Similarly, if your birthplace is actually destroyed, or in Arthur Dent’s case, demolished, ostensibly to make way for a new hyperspace bypass, then these tendrils are severed and flap about at random. There are no people to be fed, or whales to be saved. There is no washing-up to be done. And these flapping tendrils of guilt can seriously disturb the space-time continuum.

Acting is reacting is acting is reacting is acting is… you know this. You cannot react if there is nobody to react to. You can have a delayed reaction, giggling manically alone in front of your front room gas fire once you close the video conference you’ve just had to keep a straight face for, but the fact of keeping a lid on it is in itself a reaction. There is an it to lid.

In this conception of human, you do not end where your skin begins. You are not made up of whatever is in your blood and brains and kidneys and knees. You are the sum total of everything outside your physical body: what you see, smell, taste, feel and hear, who you talk to, who you have talked to, what you read or have read. You are a four dimensional creature existing as both an interpreter of the present moment and a record of every other present moment you have experienced. You are connection and interpretation.

Trippy.

So forget about crying, or whatever your equivalent hang-up is. Lost out on a job because you couldn’t do it? Never mind, there are other jobs. You might as well have lost out on one because you can’t do handstands.

By focusing on whoever it is we’re talking to and letting the record of our lives bubble up through our text and character work in whatever way it happens to on the day we’re working, we are always more interesting than the image in our heads.

NEWS

Happy St David’s! You can hear me in the excellent modern Arthuriana podcast Camlann which is set in Wales, written and directed by the admiral of fiction podcasting, Ella Watts.

I had the pleasure of working on The Nordland Railway: Tracks of War podcast by Øystein Ulsberg Brager (The Amelia Project). It’s out in full now in both English and Norwegian and tells the dark history of the building of Norway’s Nordland Railway. Episodes are short and intended to be listened to between the line’s stations.

A dangerous indulgence in a nation that, if my grandparents’ houses were any indication, still had a remarkable number of front room gas fires.

Let’s clear this up incase you too are labouring under this worry. Acting is the character in the text meeting the actor as they are on the day, not the actor as they wish to be. In extreme (and not so extreme) cases there are such things as tear sticks which make-up artists carry around in the same way they carry false beards for those who are not blessed in the chin department. If you react truthfully in the moment through the lens of all the script and character work you’ve previously done, you are acting, tick, done, impostor syndrome in the bin please.

A belt, I think.

Which means I don’t trust my director.